When the Apollo astronauts landed on the moon between 1969 and 1972, they all landed fairly close to the lunar equator.

https://lightsinthedark.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/apollo-landing-sites-new.jpg

The largest excursion north or south was that of the Apollo 15 mission. It landed 26 degrees north of the equator in the Hadley–Apennine region, almost to the rim of Hadley Rille, hypothesized to be a collapsed lava tube.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/AP_15_LS_1.png

The orbital mechanics of the Apollo missions made trips far from the lunar equator too expensive in terms of time and fuel. With even more powerful rockets than the Apollo-era Saturn V now available, there are more options.

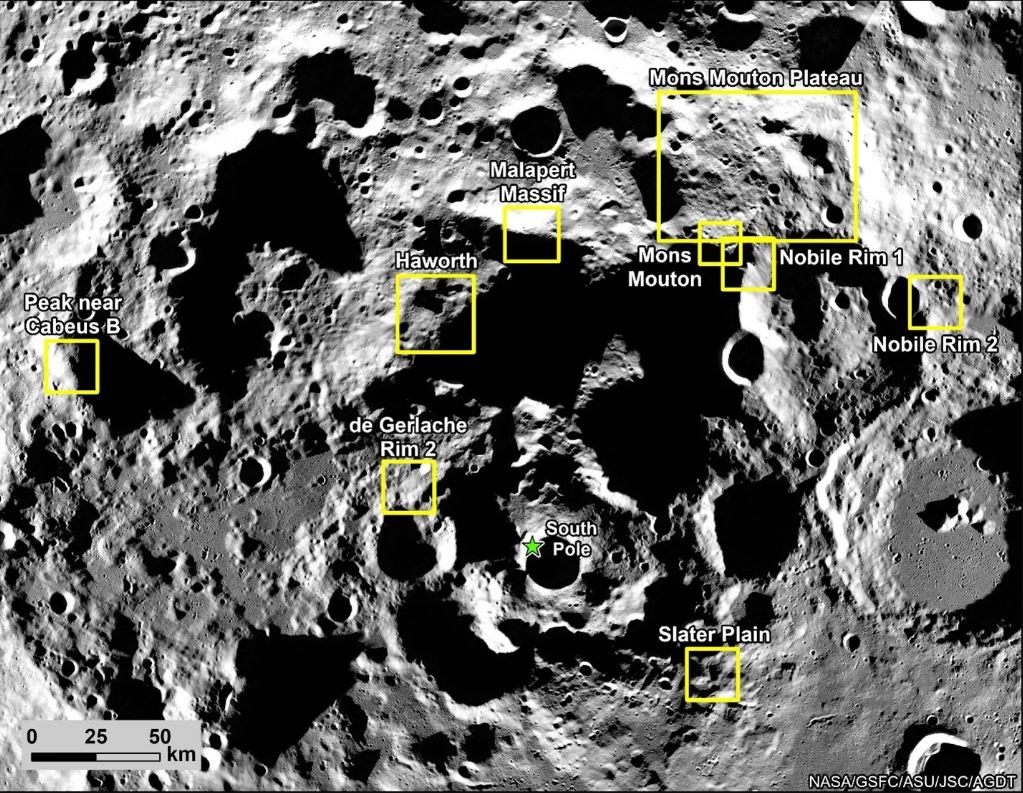

The next humans to land on the moon, whether they be in American or in Chinese spacecraft, will land farther to the south than ever before, in the moon’s south polar region. In fact, NASA has already designated potential landing sites for its Artemis III mission. Two astronauts are slated to land on the moon sometime before the end of this decade. Maybe. Much depends not only on solving engineering issues, but on the uncertainties of political decisions made in Washington. China has also announced its intention to land two astronauts at the lunar south pole by 2030.

https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/artemis-iii-landing-region-candidates.jpg

Let’s set aside for now all the complications of this endeavor, and focus on why the lunar south pole is a target for exploration.

The moon is an airless, rocky, and dry place. Its day/night cycle is 29.53 days. It bakes at up to 121°C (250°F) for almost 15 days of sunlight, and plunges as low as -133°C (-208°F) in its 15 days of darkness.

These are temperatures at the moon’s equator. But its poles have deep craters that are permanently shadowed, that never see sunlight, and that are consequently much, much colder. The interior of Shackleton Crater at the south pole averages −183 °C (−298 °F).

https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/vis/a000000/a004700/a004716/shackleton_print.jpg

Did I say the moon was dry?

Those permanently shadowed areas do have water ice in them. A NASA instrument flying on an Indian lunar orbiter detected such, and produced this map of the lunar south pole (left) and north pole (right).

https://d2pn8kiwq2w21t.cloudfront.net/original_images/imagesmoon20180820elphic20180820-16.jpg

Blue represents the ice locations, plotted over an image of the lunar surface, where the gray scale corresponds to surface temperature (darker representing colder areas and lighter shades indicating warmer zones). The ice is concentrated at the darkest and coldest locations, in the shadows of craters. [From https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/ice-confirmed-at-the-moons-poles/]

Note that because of the different topography of the two poles, there is more ice at the south pole than the north, and it is less spread out.

The two nations with the ability to return to the moon in the next decade are the United States and China. Both have continuously inhabited space stations in orbit, assembled and currently crewed with rockets launched from their territory. The remnant of the former Soviet Union’s space program simply lacks both the will and the ability to go to the moon.

The Space Race of the 1960s took place for a lot of reasons, but it wasn’t to claim ownership of valuable and limited resources. Lunar water would be useful in making long-term habitation possible on the moon. A lunar real estate agent would remind you of the classic maxim: location, location, location! A new Moon Race could be more contentious than the USA/USSR completion of the past. There is plenty of room in low Earth orbit, and no one was claiming territory on the moon, despite the planting of the U.S. flag. This time it could be different.