When all you have is one example, it’s interesting to speculate but hard to draw conclusions.

How Common Are Planets?

For most of my lifetime, we only knew of one star hosting a planetary system: ours. Were the conditions that allowed Sol to host planets from Mercury to Neptune, and smaller objects from rocky remnants to distant ice balls, common? Unusual? Unique?

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/19/Solar_System_true_color.jpg/1280px-Solar_System_true_color.jpg

As we began to better understand how our own planets were formed, and were able to detect signs of incipient formation around other stars, It seemed more and more likely that at least some other stars were orbited by planets, too. This would fall in line with something called the Copernican Principle, which holds that we occupy no special or privileged spot in the universe. It’s anthropocentric, even egotistical, to assert that we are anything out of the ordinary.

Beginning about 30 years ago, we began to acquire instruments, both ground based and space based, sensitive enough to detect the presence of planets around other stars, exoplanets. At present there are more than 5,000 exoplanets whose existence has been confirmed, and thousands more “candidate” detections that require further observations. Planets are indeed common. It seems that, as one study concluded, “…stars are orbited by planets as a rule, rather than the exception”.

How Common Is Life?

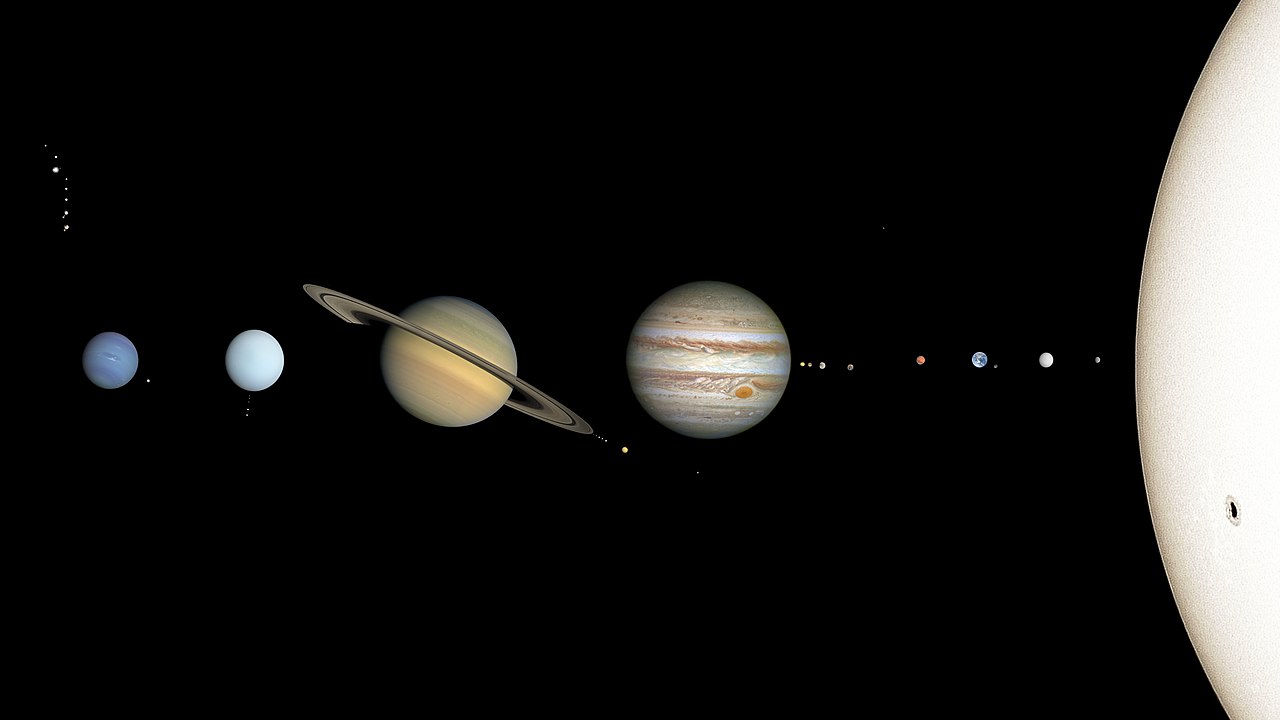

The one example we have for the presence of life arose on a planet. While it’s at least conceivable that extraterrestrial life could have an entirely different chemistry from our own, it seems unlikely. After all, hydrogen, oxygen, and carbon are among the most abundant elements present in the universe. Water and carbon-based life on a planetary surface is “life as we know it,” and looking for conditions that can support that is a logical search strategy. That means searching for rocky planets orbiting their stars in the “habitable zone”, something of a Goldilocks region that is neither so hot that water boils away nor so cold that it all freezes into ice. We need liquid water, a rocky surface, and an atmosphere that can provide the pressure needed to maintain water as a liquid.

https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/06/3habitable_zone-en.jpg

You’ll note from the diagram that larger and hotter stars will have habitable zones farther away from the star, while smaller and dimmer stars require planets to huddle close for sufficient warmth.

But of course there are other factors. The largest and hottest stars are also the shortest-lived. Our star Sol is midway between the largest and the smallest stars; it is roughly 5 billion years old, with another 5 billion to go before it exhausts its nuclear fuel. The largest stars last only 5-10 million years. That’s a long time for humans, but a mere eyeblink in the history of the universe.

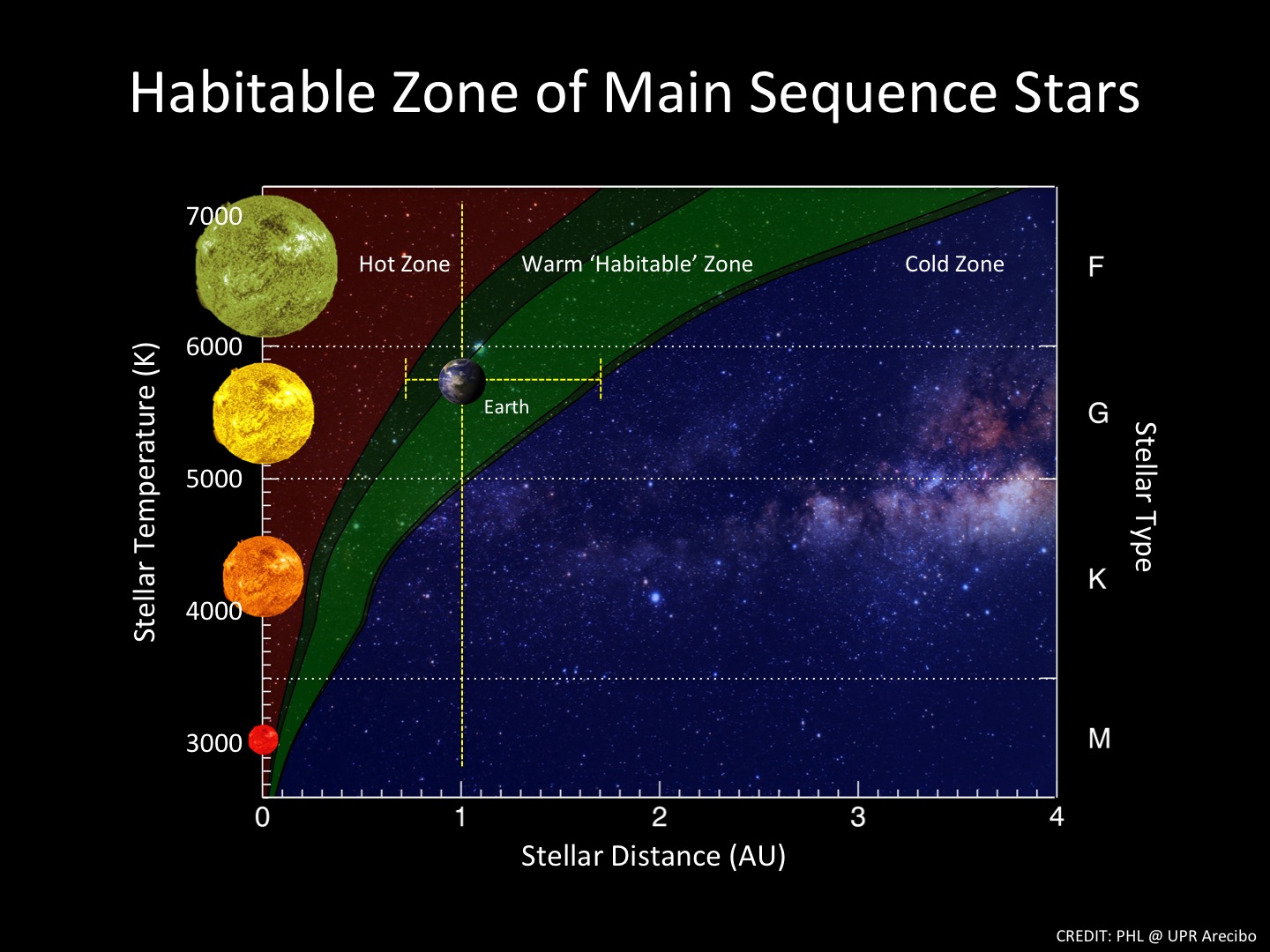

No one knows exactly how or when life arose on Earth from inanimate matter, but it seems that happened about a billion years after the planet’s formation. Another three billion years passed before life moved from single cells to multicellular organisms. And the kinds of brains that can build spacecraft and telescopes capable of detecting exoplanets are very recent developments.

https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiVNSbqgZRNc5ZO3EesCMyrv_newUoLkT02nVYFfy8dQFfoXU4PO101-jw6x-2DX2DnZzS5NxL3K_pscgE_zusrRvnBtfK0GZeVmVPCSven6dwWEDjRR-a2n1R9jREurcx6F2hyphenhyphenNu0rVo4/w640-h496-rw/the-geological-time-scale+%25281%2529.jpeg

The immediate conclusion would seem to be that our best bet for finding worlds where not only are the conditions favorable for the emergence of life, but where those conditions existed for long stretches of geologic time. Sun-like stars and stars smaller and cooler than the sun, in other words. There are far more of these smaller stars than larger ones.

What makes a planet potentially habitable?

Once again, there are complicating factors! The habitable zone of the smaller stars is so close to the star that tidal locking of any planet orbiting there is almost certain.

With one side constantly facing the star and the other facing away into interstellar space, there would be extreme temperature differences between the two hemispheres. These stars are also quite variable in their luminosity, and subject to violent flares. Imagine the heating and cooling system in your house cycling unpredictably between Phoenix in July and Helsinki in January!

Detecting an Earth-like planet around a Sun-like star is difficult for any number of reasons, and will remain so for some years to come. And we are only barely able to determine whether a planet might be habitable, not whether it actually harbors life. Nonetheless, there are some candidates. With somewhere between 100 and 400 billion stars and at least an equal number of planets in our own Milky Way galaxy, it’s hard to imagine that they are all devoid of any form of life.

There is a long list of potentially habitable planets that you can find here. Note that exoplanets are named with the name of the star followed by b for the first planet discovered orbiting that star, c for the second, and so on.

Let me just highlight one planet and one planetary system of particular interest.

Proxima Centauri b is an Earth-size planet that orbits the star that is nearest to us, only 4.2 light years away. The star is a small and cool red dwarf, orbiting the other two larger and brighter stars of this triple system at some distance. The habitable zone in which the planet resides is very close to the star. Orbiting only 4.5 million miles away (Mercury orbits our sun at a distance of 29 million miles at its closest), it is almost certainly tidally locked. And Proxima Centauri is a flare star, emitting powerful radiation that could well strip off any atmosphere the planet might possess. Still…it’s close!

https://universemagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/universe_no.2_2021_eng-1024×499.jpg

https://cdn.sci.news/images/enlarge3/image_4130_3e-Proxima-b.jpg

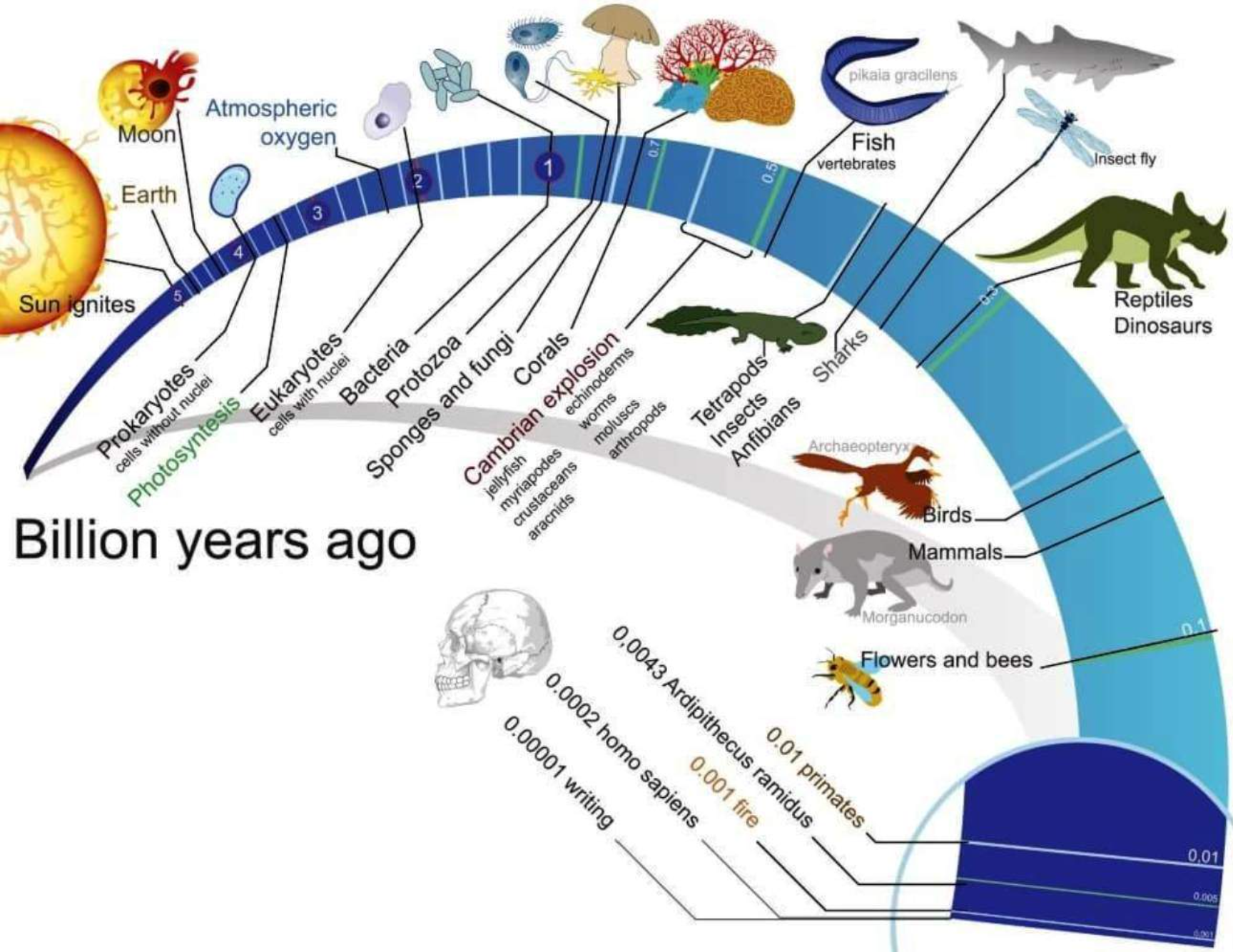

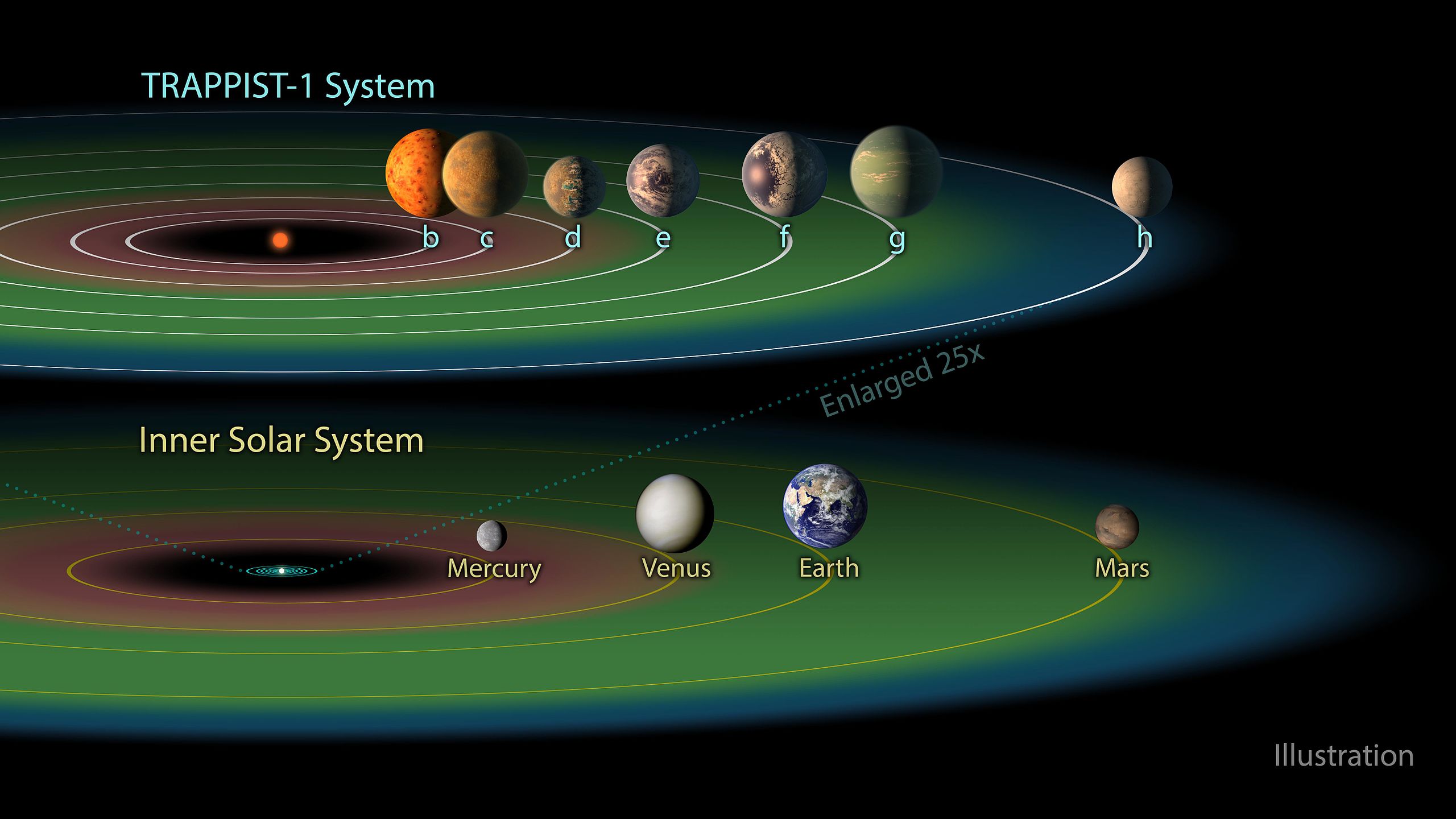

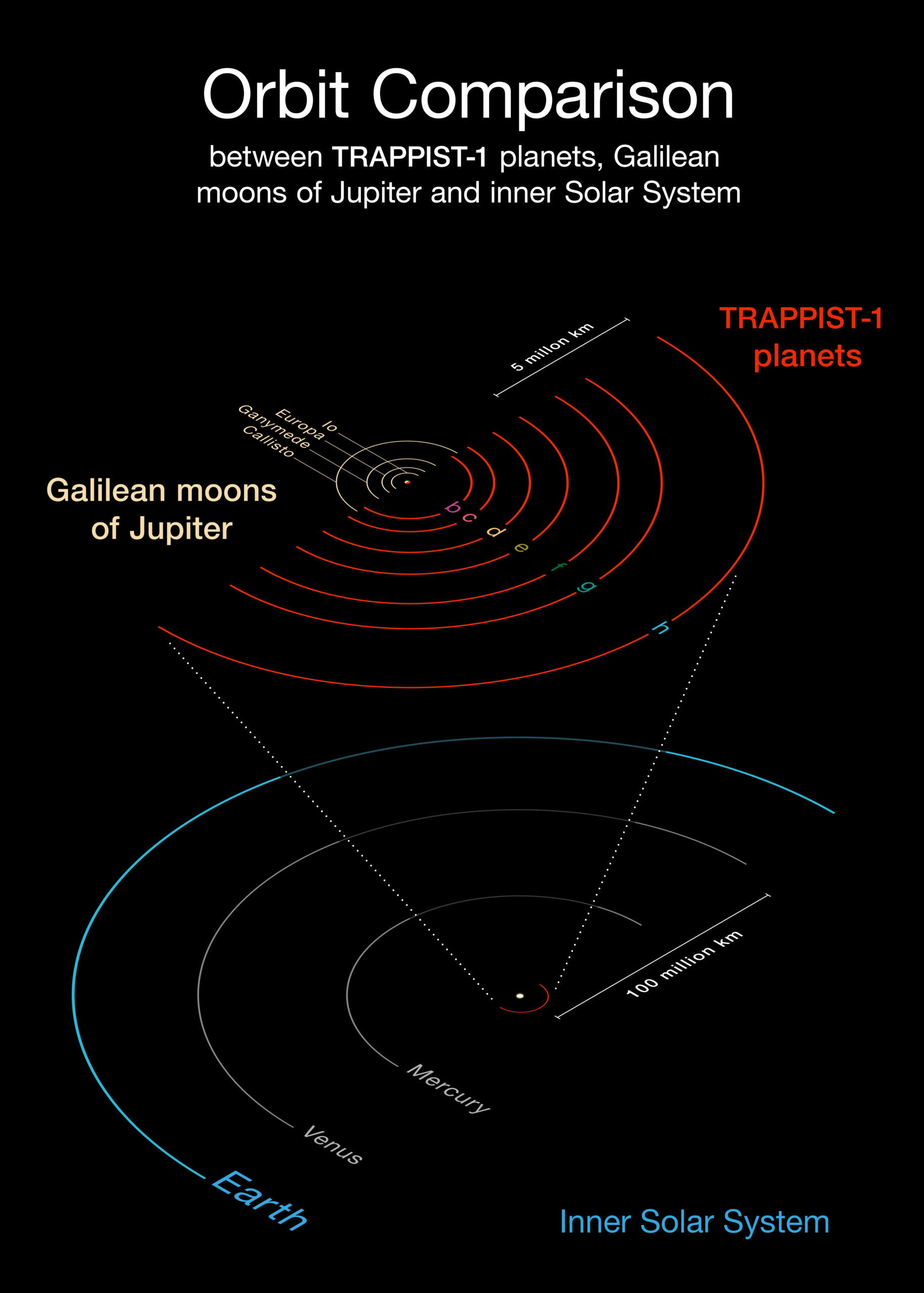

Trappist-1 is a very small and cool star 41 light years away. It turns out to have seven planets! Three of these are in the habitable zone.

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/f7/PIA21424_-_The_TRAPPIST-1_Habitable_Zone.jpg/2560px-PIA21424_-_The_TRAPPIST-1_Habitable_Zone.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/19/Comparison_of_the_TRAPPIST-1_system_with_the_inner_Solar_System_and_the_Galilean_Moons_of_Jupiter.jpg